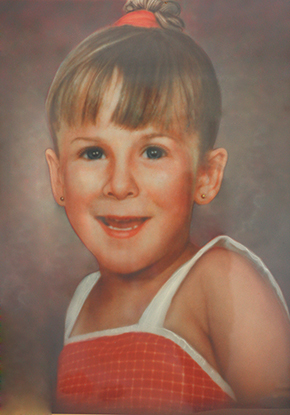

Glenmore Park’s Jurina Hickson has been haunted for the past 35 years by the immeasurable pain of the murder of her little daughter at the hands of a callous killer.

But that pain hasn’t daunted her determination to urge Governments State and Federal to protect families and children, as more and more reports of violence and abuse emerge.

“They have to do something,” she told the Weekender this week.

“The people have to demand it.”

The person who killed four-year-old Lauren Hickson in 1989 is dead. He died in jail two days before his possible release on parole.

“Thank God he’s gone. He can’t hurt any more children. He can’t hurt my family again,” she said.

“But I still don’t have closure. I think of Lauren. I think of what she may have become – would she have married? Be a wife? A mother? I just don’t know.”

35 years on from the murder, Jurina and husband Derek are currently facing the tough times of all pensioners across western Sydney – health issues, the rising cost-of-living. The struggle to get by. Always with the memory of their lost baby in the background.

The torture, rape, bashing and murder of four-year-old Lauren Hickson on May 17, 1989, at the Nepean Caravan Park at Emu Plains casts a dark stain on the Penrith community that can never be erased.

It has also left dark and brooding imaging on those who came into close contact with the killing, the sight of the tiny victim’s lifeless body, the trauma of the investigation by three experienced local police officers, even the media who attended the scene and the subsequent court proceedings, and, of course, the terrible toll it has taken on Jurina and Derek, and Lauren’s then 14-year-old sister Tracey.

The facts of the crime are terrible to record.

Wednesday, May 17, 1989, 1.30pm. Then 23-year-old Neville Raymond Towner lures four-year-old Lauren to a secluded area along the river bank, strips her, and attempts to rape her, terrifying the little girl.

“She wouldn’t stop screaming, so I put her head under the water,” he would tell Homicide Squad Detectives Warwick Laney and Steve Ticehurst later in a record of interview.

“How long did you hold her under the water?” Laney asked.

“A couple of minutes. To shut her up. I shoved her head in the water. And when she came back up she looked to me as if she had gone already and I hit her in the head with a rock.”

For the Hickson family, that May day began normally, with Jurina and Lauren alone at home, Derek at work and 14-year-old big sister Tracey at school. Lauren was riding her new pushbike around the family’s cottage.

At Midday, Jurina sat down to watch long-running daytime TV show, ‘Days of Our Lives’, a personal favourite of hers.

“The whole case could be described as ‘The Days of our Lives’ crime,” Ticehurst recalls nowadays.

“Jurina was getting ready to watch that soap opera on the telly as she did each day. So was her next door neighbour, Helen Hibernet. Both saw Towner ride past on his pushbike.

“So did a local bloke whose brother was a ‘Days’ fan (Gary and Guy Taylor) but had forgotten to set his VCR to record that day’s episode and sent him to the caravan park to push record on the VCR. He also saw Towner ride by. Each of these witnesses was able to give us the exact time Towner arrived there.”

Show over, Jurina heard Lauren chatting with Neville Towner, the son of one of her friends from the local Salvation Army Citadel, and sometime babysitter for her children.

But by 2.15pm she became concerned that Lauren had not been seen nor heard from in some time.

She searched and called to no effect, and as time ran out, desperately called for help from police, with her call logged at 5.23pm.

Police, State Emergency Service members, military personnel, park residents and volunteers gathered for a search party numbering more than 100.

All feared the little girl had fallen into the Nepean River, swept away by the current.

Police officers canvassing the residents soon learned that Towner had been seen with Lauren between about 1.30pm and 4.30pm. One witness told police she saw Lauren approach Towner, hug him, and the pair walked past her mobile home.

Investigators brought Towner in for questioning. But when he made a statement denying any knowledge of what happened to Lauren, they released him.

The search resumed the next day. After several hours, as Jurina sat with Ticehurst and Laney and other police at the search command post, a Channel 10 news crew spotted clothing in a tree, and alerted the search team, which included Police Rescue Squad officer Paul Kelly.

As he meticulously scoured the surrounding area, Kelly made the grim discovery in a riverbank waterhole.

“I reached down into the water,” he recalled.

“I took her by the ankle and raised her up on to the bank. Picked up my radio and called into the command centre.

“I’ve found her. Deceased.

“Then I heard a woman screaming. I did not know her mother was with the detectives.

“That scream has stayed with me ever since. I will never forget that sound.’’

News cameraman Scott Richardson, a veteran news-gatherer, also recalls that moment. He watched through the viewfinder of his camera as the tiny body swung in the air, as Kelly gently laid her on to the grass, with a sobbed “No, stop, don’t,” to the news crew.

“That image is forever etched on my mind,” Richardson said.

“I covered many murder stories, including the discovery of murdered women such as Janine Balding, Anita Cobby, and others, before and after the murder of Lauren.

“But that scene, that day. I will never forget it.”

Ticehurst also has vivid memories of the crime scene.

He does not hold back in describing the crime, and Towner.

“It was a despicable thing that he did for sexual gratification and robbed her of her life,” he said.

The detectives returned to Towner’s Kingswood home, taking him into custody to Penrith police station.

Ticehurst said at the station, Towner made full admissions to the crime, but unfortunately the young constable who took it down failed to issue the judicial warning and his notes could not be used in court.

Laney and Ticehurst also carried out a full record of interview with Towner in which the killer described his every movement.

By the end of the day Towner faced charges of assault, attempted rape and murder, and was refused bail to face Penrith Court on Friday, May 19.

There, a crowd gathered, one man displaying a child’s doll with a noose around its neck.

Towner went to trial in the NSW Supreme Court in 1992 – convicted of the attempted rape and murder of Lauren Hickson, sentenced to life in prison with no possibility of parole.

For the family, the relief was enormous.

“He is an evil man,” Jurina Hickson told reporters at the court.

“He won’t be able to hurt any other child ever again.”

But her relief proved short lived. Towner began a series of appeals and applications to the State Parole Board for a release date. Each hearing an ordeal for Jurina and Derek, as they attended to hear their lawyer put their submissions for parole to be refused.

“I just don’t want him coming after my family again, I don’t want him coming after anybody,” she told reporters.

“He’s a ticking time bomb.”

Eventually, Towner won the possibility of a release date, despite the impassioned pleas of Jurina, the arresting police, and a petition with 150,000 signatures.

The Board planned to make its decision public on June 29, 2018. But on June 27, 2018 news emerged that Towner had died in Long Bay Jail.

Ticehurst recalls the moment he heard the news.

“I was watching the Channel 7 news one night when I received a call from my nephew in Queensland. He informed me that Towner had passed away,” he recalled.

“I rang Channel 9 reporter Simon Bouda who confirmed through prison officials that Towner was dead.

“It was such a relief that this mongrel died in gaol. He did not deserve to be released nor walk the streets. He committed one of the worst crimes against a child and should never have been considered to be released by the parole board.”

Jurina Hickson recalls being stunned when she heard the news.

“I said I can’t believe he’s gone, he’s gone, he’s gone,” she said.

“Good riddance to bad rubbish.”

A subsequent inquest in 2020, before Deputy State Coroner Elaine Truscott found Towner’s cause of death was Respiratory Distress Syndrome.

In simpler terms, Towner died of natural causes whilst in the lawful custody of Corrective Services NSW.

Despite the passing of 35 years, Jurina still has a vivid and emotional clear memory of her final sight of little Lauren.

She speaks quietly. Her words clear. The emotion obvious.

“I went to the funeral parlour and demanded to see her,” she said.

“They didn’t want to show her to me, but I demanded to be allowed to.

“They brought her out, her face covered. I moved the cloth and saw what he’d done to her. She’d been sexually assaulted.

“I bent down and kissed her.

“She was cold.

“I never saw her again.”