Beaten, raped, disowned and institutionalised; this is the story of Sandie Jessamine.

A remarkable tale of survival and endurance, as she revisits her time at the Parramatta Girls Home and her troubled life as a misunderstood teen.

Ms Jessamine says she never truly felt like she belonged.

Adopted at birth into a prestigious family she was quick to be labelled “uncontrollable” and “wild” by her adopted parents – a behaviour that only escalated after an attempted rape by a friend’s brother at just 12-years-old.

Her cries for help were met with denial, shame and packed bags, as she was sent off to institutions for ‘delinquent girls’ in order to control her behaviour.

She was eventually sent by a children’s court to Reiby Training in Campbelltown.

“I was 14-years-old when I was first locked up and remember just feeling completely out of my depth, being among these young criminals and prostitutes,” Ms Jessamine said.

“The first thing that happened when you arrived back then was being shunted off into a clinic, being told to spread your legs and undergo an internal examination which was really horrific.”

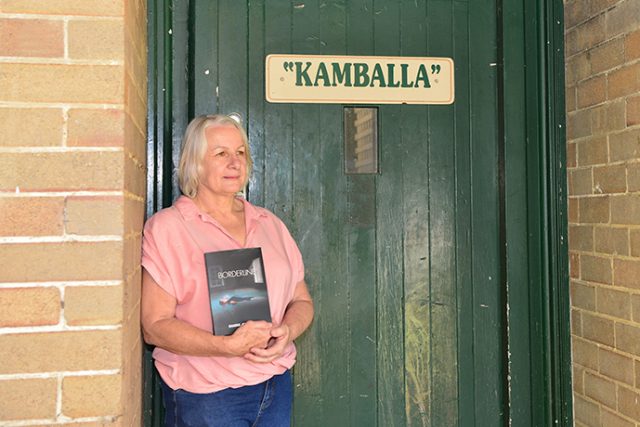

When her behaviour did not improve, she was transferred in 1974 to Kamballa Special Unit at Parramatta at 15-years-old.

Kamballa was the new name for the Parramatta Girls Home, a state-controlled child-welfare institution.

Ms Jessamine tries to describe the harrowing ordeals she endured inside its walls but some of her memory is foggy; something she has later learned in life is due to her complex post-traumatic stress and borderline personality disorder that saw her frequently dissociate as a young girl.

“When I got to Kamballa there were only two girls there, one who was a murderer and another was this wild little street kid who had been locked up since she was 12-years-old,” she said.

Ms Jessamine shared a room with the infamous convicted child killer – a young girl who quickly became a friend and an accomplice in their escape just six weeks after arriving.

The pair and four other inmates scaled a three metre high brick wall and swam across the Parramatta River to escape.

The escape made front page news as the girls hid in Kings Cross before splitting up and being recaptured by the police.

Bashed violently in police custody, Ms Jessamine’s mental health continued to steeply decline, particularly upon her return to Kamballa where girls blamed her for the capture of another escapee.

“Kamballa turned into a nightmare for me at this stage. I kept blacking out, I would be in one spot and wake up in another and that’s when I escaped again,” she said.

Scaling the wall for a second time, Ms Jessamine successfully escaped and lived on the streets of Redfern.

However it was here she was exposed to a new world; one of muggings, stealing, violence, drinking and drugs.

Things came to a head when she was violently raped, picked up by police and returned to Kamballa.

It was then she made a pact with herself to survive, turn her life around and never get locked up again.

Remarkably she went on to complete a Master of Education and worked in NSW prisons as a creative writing teacher for 15 years.

“For two years I worked at Parramatta men’s prison and would have to walk past the girls home every day but I would dissociate so much that it just wasn’t there to me,” Ms Jessamine said.

In 2015 things went downhill, following a breakdown and the passing of her daughter.

As part of her recovery, she decided that to be able to move forward, she must go back to the place that robbed her of so much joy.

Revisiting the space that once imprisoned her was a confronting feeling, she said, one that felt like a distant memory she had kept locked in the back of her mind for decades.

She began writing as a form of therapy and has recently published a memoir titled Borderline.

The book tells her unique and compelling story, beautifully capturing all of the different voices that live within her, as she depicts what life was like for young girls who slipped through the cracks in the 1970’s.

“I now own who I am, my disorders and all,” Ms Jessamine said.

“I used to see it as something negative but now I realise my ability to switch states it what kept me alive.

“Going insane may have been the sanest thing I ever did.”

Borderline is available now at Booktopia, Amazon and all good book stores across Australia.

If you need support, call Lifeline Australia on 13 11 14.

Nicola Barton

A graduate of Western Sydney University, Nicola Barton is a news journalist with the Western Weekender, primarily covering crime and politics.